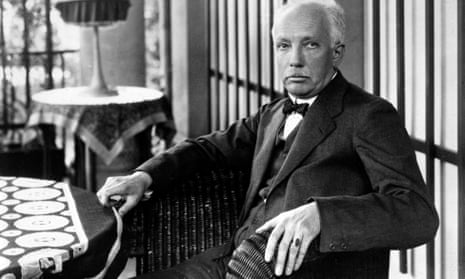

Richard Strauss (1864-1949) dominated classical music at the turn of the 20th century with a series of works that pushed post-Romanticism to extremes and pre-empted the innovations of modernism. He, however, never embraced atonality, and was ultimately a pragmatist for whom subject matter always dictated style and harmonic language. One of the greatest of all opera composers: few have quite so profoundly understood the expressive power of the human voice or written for it so superbly.

The music you might recognise

Stanley Kubrick’s use of Also sprach Zarathustra in 2001: A Space Odyssey has made it the most immediately recognisable of Strauss’s scores, heard in countless parodies and imitations since. Though not related to Johann Strauss II, Strauss was proud to share the same surname, and his waltzes from the opera Der Rosenkavalier have become almost as popular as those of his namesake.

His life

He was born in Munich, the son of a horn player at the court opera, who admired Beethoven and Mozart (who Strauss also considered the greatest of composers), but loathed progressives such as Liszt and Wagner. Strauss’s mother suffered from episodes of mental illness that later found echoes in Strauss’s own treatment of psychological extremes in his work. He began composing aged six, and his subsequent training was informally undertaken by his father’s colleagues.

In 1884, his Serenade in E Flat for 13 wind instruments brought him to the attention of influential conductor Hans von Bülow, who immediately commissioned its sequel, the Suite in B Flat, with which Strauss made his conducting debut, also in 1884. The following year, Bülow appointed the 21-year-old as his assistant conductor in Meiningen. From then until 1924, Strauss combined composition with a series of increasingly important conducting posts as his reputation grew.

His first works marked him out as a potential traditionalist but during his early 20s, he studied Liszt and Wagner’s music and rebelled against the classical constraints fostered by his father, becoming famous overnight in 1889 with the premiere of Don Juan, a work of unprecedented hedonism. It was the first of the series of tone poems that dominated his output for the next decade and includes Tod und Verklärung (1890), Till Eulenspiegel (1895), Also sprach Zarathustra (1896), Don Quixote (1898) and Ein Heldenleben (1899).

Zarathustra was based on Nietzsche’s book of the same name; Strauss considered the philosopher his greatest intellectual influence. Ein Heldenleben, begun shortly before Strauss’s appointment as Wilhelm II’s kapellmeister (music director) in Berlin, caused a controversy: Strauss identified himself, by means of quotations from his own music, as the hero of his own tone poem, resulting in charges of opportunism. Ein Heldenleben also contains Strauss’s first musical portrait of his wife, the temperamental soprano Pauline de Ahna for whom he wrote many of his finest songs (one of the best known, Morgen! was a wedding present). His first opera, Guntram was a failure at its 1894 premiere but its successor, the risqué comedy Feuersnot, proved more successful in 1901.

The 1905 premiere of Salome, however, marked a major turning point. Based on Oscar Wilde’s play, it depicts its heroine’s sexual awakening in a world so corrupt that her desire can only find eventual fulfilment in necrophilia. The score still astounds with its mix of beauty, dissonance, ecstatic lyricism and violence. Though it caused enormous controversy, it established Strauss’s operatic reputation and made him rich: the royalties enabled him to acquire the villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Bavaria that was to be his home for much of his life.

Elektra (1909) was even more extreme – dark and metallic in tone, the harmonic language veering at times towards atonality in Strauss’s depiction of the guilt-ridden murderess Klytämnestra. The opera’s source was an adaptation of Sophocles by the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Strauss’s request for his help with the libretto set in motion one of the great partnerships in operatic history.

… and times

Elektra was written contemporaneously with the growth of the psychoanalytic movement and is frequently discussed in reference to it: Klytämnestra, racked by nightmares, has been compared with a patient seeking an interpretation for her dreams, while the character of Elektra herself, fixated on revenge for her father’s death, can be viewed as a study in obsessional neurosis. We have no indication, however, that Strauss ever read Freud’s work, though Hofmannsthal was familiar with Studies on Hysteria, published in 1895.

Their next collaboration was Der Rosenkavalier (1911) a bittersweet, nostalgic comedy of manners set in 18th-century Vienna that consciously alludes to Le Nozze di Figaro: its hero, Octavian, is modelled on Mozart’s Cherubino and similarly played by a soprano or mezzo. Running through it is an ambiguous sense of time slowly eroding human lives and relationships. Though the harmonic language is at times as dissonant as anything Strauss ever wrote, some critics saw it as a refutation of modernism.

Strauss was never to equal its success in his lifetime. The experimental Ariadne auf Naxos, the stage work that followed, frames a chamber opera with an adaptation of Molière’s play Le bourgeois gentilhomme, for which Strauss also provided incidental music. It drew a blank with audiences at its 1912 premiere, and Strauss and Hofmannsthal eventually replaced the play with a fully sung Prologue. The revised Ariadne was first heard in 1916, by which time Europe was at war.

Hofmannsthal was called up, and Die Frau ohne Schatten, begun before the opening of hostilities, was placed on hold. Strauss (who was too old for active service) returned to the sketches of a tone poem begun in 1911, which became the tremendous Alpine Symphony (1915). Frau, a vast phantasmagoria about desire, marriage and procreation, was completed in 1917, and first performed in 1919 in Vienna, where Strauss had been appointed artistic supervisor of the Staatsoper, a post he resigned in 1924, amid accusations – seemingly not entirely unjustified – of financial mismanagement and allegations he was shamelessly promoting his own works.

In the 1920s, he struck out on his own with Intermezzo (1924), an autobiographical comedy to his own libretto, before turning back to Hofmannsthal for Die ägyptische Helena (1928), a complex parable about the aftermath of the Trojan war, and, by implication, the first world war also. Their last opera was another bittersweet Viennese comedy, Arabella. Hofmannsthal died suddenly in 1929 before revising the libretto’s final acts, which Strauss set in tribute as they stood. His choice of successor fell on the Austrian-Jewish novelist Stefan Zweig, with whom he worked on the comedy Die schweigsame Frau, but almost from the outset, their relationship was affected by the rise of nazism.

Strauss initially seemed to play into the Nazis’ hands by deputising for a number of conductors forbidden from performing, and late in 1933, accepted the presidency of the Reichsmusikkammer, set up by Goebbels to oversee the Reich’s musical activities, though he never put any of the Nazis’ antisemitic policies into practice. He was dismissed in 1935, when a letter to Zweig that was sharply critical of the regime was intercepted by the gestapo. Die schweigsame Frau was banned after its first run the same year. Strauss’s daughter-in-law Alice, and therefore her two sons, were Jewish, and from 1938 onwards, Strauss and his family were subject to repeated intimidation. His grandsons were eventually given honorary Aryan status, but Strauss was unsuccessful in his attempts to obtain the release of other members of Alice’s family held at Terezín, many of whom were murdered.

He continued to compose, working with Austrian theatre historian Joseph Gregor for Friedenstag, the astonishingly beautiful Daphne (both 1938) and the unwieldy Die Liebe der Danae. With conductor Clemens Krauss he collaborated on Capriccio (1942), a “conversation piece for music,” which constitutes a guarded demand for artistic integrity and continuity in dark times. As the second world war drew to a close, he composed the harrowing Metamorphosen (1945) for string ensemble, thematically linked to the Funeral March from Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony.

After the war, he turned to absolute music, ie music without literary, programmatic or dramatic associations. A chance encounter with an oboist serving in the allied forces resulted in the exquisite Oboe Concerto (1946), while his lovely Duet Concertino for clarinet and bassoon dates from 1947. Aware that he would have to face a de-nazification tribunal, he and Pauline went into voluntary exile in Switzerland, returning to Germany after his acquittal in 1948. His last completed work was the Four Last Songs, a quiet farewell to life and the final expression of his deep love for his wife.

Why he still matters

In the years immediately after his death, Strauss’s reputation fluctuated, though the major tone poems, together with Salome, Elektra, Rosenkavalier and the Four Last Songs remained hugely popular. Starting in the 1960s, however, the gradual re-evaluation of his output resulted in many more of his works becoming central to the repertories of orchestras and opera houses worldwide. Many would today argue that the psychological understanding apparent in his operas rivals that of his beloved Mozart, and few would doubt the power of his music to overwhelm and enthral.

Great performers

Fritz Reiner, Rudolf Kempe and Herbert von Karajan’s recordings of the tone poems are widely considered benchmarks. Karajan’s and Karl Böhm’s performances of the operas have similarly been hugely admired, though Erich Leinsdorf’s Salome is utterly chilling and Elektra is perhaps best served by Dimitri Mitropoulos in two terrifying live recordings. Erich Kleiber’s Rosenkavalier remains a classic, as does Kempe’s Ariadne auf Naxos. The tremendous list of Strauss singers includes Lotte Lehmann (whom he regarded as his “ideal interpreter”), Irmgard Seefried, Ljuba Welitsch (for some the definitive Salome), Leonie Rysanek, Gundula Janowitz, Leontyne Price, Christa Ludwig and Renée Fleming.

Next week: an overview of some of the many composers we haven’t written about…

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion