Even if you don’t know his name, chances are you’re familiar with Robert Crumb’s cartoon art — that scritchy-scratchy, overly rendered linework adorned with masterful cross-hatching that creates unparalleled texture and shadow.

Maybe you’ve encountered his myriad creations: horny feline Fritz the Cat; those “Keep on Truckin’” dudes with the elongated left legs; that “Stoned Agin!” poster with the melting hippie; the domineering Devil Girl, her thighs thick as tree trunks; or the voluminously bearded Zen master Mr. Natural.

Perhaps you’ve come across his numerous New Yorker covers and interior strips, or his collaborations with “American Splendor” crank Harvey Pekar.

“Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life,” by Dan Nadel.

Maybe you’ve seen the man himself: that scrawny, bespectacled weirdo in a cardigan and fedora, with a perpetually nervous mien.

Or perhaps you’ve watched the award-winning 1994 documentary “Crumb,” which examined the artist’s neuroses, peccadillos and obsessions — the latter revolving mostly around sex and old-timey jazz records — when it wasn’t training its lens on his fascinatingly dysfunctional family.

In the 30 years since the film’s release, much has transpired in the life of the man many consider to be one of the greatest comics artists — or, just simply, artists — of our time. And Dan Nadel’s new biography, “Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life,” traces it in remarkable, forensic detail: his love life, his drug intake, his finances and, most important, his extraordinary body of work.

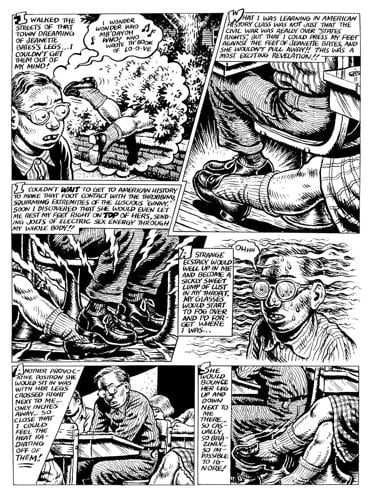

Meet young Robert Crumb ... when sturdy legs strode into his mind to stay

It’s the first major biography of the artist — one created with his full co-operation. As Nadel admits in his introduction: “Robert imposed just one condition on this book: that I be honest about his faults, look closely at his compulsions, and examine the racially and sexually charged aspects of his work.”

Does he ever.

Nadel meticulously details Crumb’s childhood, starting with a household headed by an abusive military-man father and co-starring a mentally unstable mother, two sisters and a pair of troubled brothers.

When the budding illustrator discovered a 1956 copy of Mad magazine — drawn to its rude humour and anarchic spirit — he had an epiphany: this is what he would do with his life. His early professional career found him drawing greeting cards alongside Ziggy creator Tom Wilson and later assisting a pre-Monty Python Terry Gilliam on a humour magazine.

An autographical moment of pubescent awakening from cartoonist Robert Crumb’s 1988 story, “Footsy.”

Crumb’s own comics were exquisitely rendered, funny and self-flagellating — sometimes profound — a forum where he could air grievances both mundane and imperative, based on a world view shaped by acid. LSD, Nadel writes, “had opened a channel into his subconscious that ushered in ideas whose real meanings were a mystery even to him.”

In comic books with titles like “Zap,” “Snatch” and “Uneeda,” no personal kink was too outrageous to illustrate. As Nadel convincingly asserts, “It took a long time for Robert to realize that women might have some agency in his fetishes — that they were there for it as much as he was. He was more likely to view women as all sexually ‘normal’ and himself as a creep, thereby satisfying his own self-loathing and need for domination.”

“Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life” also functions as both a travelogue through America’s ’60s counterculture and a brilliantly concise history of the underground comics scene that sprang from it, an indie movement that inspired the likes of Daniel Clowes, Alison Bechdel and Chester Brown.

It was a time when comics artists first owned their creations, Nadel writes, “in some cases controlling the printing and distribution as well.” But Crumb, often struggling for cash, also got burnt by bootleggers who reproduced his work on merchandise without permission or remuneration.

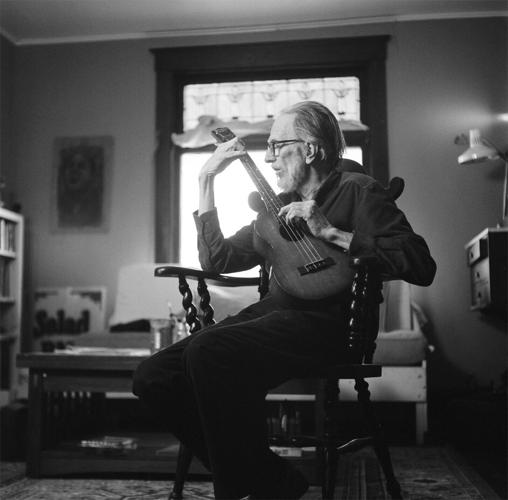

Dan Nadel, author of “Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life,” is also a museum curator.

Nadel excels when critiquing Crumb’s work, scrutinizing his use of racist tropes that clashed with his otherwise earthy, progressive ideals, and smartly describes the artist’s technique free of jargon. Remarking on the change in style Crumb brought to “Zap,” Nadel writes, “Robert was now using a crow quill pen, which allows artists to control their line density, moving from thick to thin in a single stroke, giving weight and drama to objects and scenes by adjusting their pressure on the page.”

The author’s extraordinary access to Crumb and his family and friends also results in some startling passages. Describing one particularly vivid acid trip taken by Crumb and his first wife, Nadel writes, “Dana felt she was passing through the birth canal. Unfortunately, what she thought was amniotic fluid was Robert vomiting on her.”

Lavishly illustrated, with personal photos (thankfully, none from that trip) and numerous examples of his work, “Crumb” is a terrific biography that just misses being a great one. It’s let down, as too many books are these days, by lax copy-editing, which invites errors, clichés and grammatical mishaps onto the pages.

For one, Industry City is a neighbourhood at the western edge of Brooklyn, not the eastern, something Nadel, a Brooklyn-based museum curator, must know. And a quote from Crumb’s second wife, Aline, misnaming comedian Joey Bishop as “Jose,” goes uncorrected.

Comparing the thickness of eyeglasses to Coke bottles once should be verboten; thrice should be illegal. Paragraph-long quotations sometimes go uninterrupted and unattributed. And someone should have caught the dangling modifiers that pop up all too often. (“With a new baby to care for, Clayton Street couldn’t be a hippie crash pad,” Nadel writes, raising the question: how can a road have a child?)

Still, this handsome book belongs on the shelf of all Crumb fans, and anyone curious about the early days of independent publishing will find much to love.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation