Readers and activists who have been inspired to global political consciousness by such influential books as Culture and Imperialism and Orientalism might be surprised to learn that their author, Edward W. Said (1935–2003), was also an astute scholar of music and a classically trained pianist whose publications include Musical Elaborations and Music at the Limits.

A prominent pro-Palestinian advocate, and a tenured Columbia University professor, in the years not long before his death, he joined with Argentine-born concert pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim to establish the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, a project bringing together young Arab and Jewish musicians on an equal playing field to grow their skills in musicianship and performance. Forced to move their efforts outside of apartheid Israel-Palestine, the foundation brought students to Spain to study together. In 2016, the Barenboim-Said Akademie opened its doors in Berlin to scholarship students from all over the Middle East—a dream Barenboim calls “an experiment in utopia.”

Longtime readers of The Nation magazine may recall Said’s insightful music criticism from 1986 to 2003. In fact, stage genius Peter Sellars, in “Edward Said’s Inner Music,” his incisive prefatory essay to the new book, refers to Said’s earlier interest in opera as, like anything else, implicitly related to the larger workings of society:

Longtime readers of The Nation magazine may recall Said’s insightful music criticism from 1986 to 2003. In fact, stage genius Peter Sellars, in “Edward Said’s Inner Music,” his incisive prefatory essay to the new book, refers to Said’s earlier interest in opera as, like anything else, implicitly related to the larger workings of society:

“One of Edward’s most brilliant excursions into writing about opera arrives midway through Culture and Imperialism, when he undertakes an anatomization of Aïda and excavates the original process of creating the characters, the libretto, the scenery, and the music as a colonialist enterprise of shocking proportions. He doesn’t say much about the music [by Giuseppe Verdi], but I’m sure that he, growing up in Cairo, had little patience for this opera and its falsification of histories, lives, and issues that are appallingly still underrepresented, unresolved, and falsified by various credited and discredited regimes today. The occasion for the commissioning of Aïda was, famously, the opening of the Suez Canal, a moment of colonial self-congratulation that entailed the building of an entire opera house in which to premiere the work, launching an architectural Europeanization of one half of the city of Cairo, which was razed and rebuilt to more resemble Paris.”

It is social criticism on this level (casually called “woke”) that has led large organizations such as the Metropolitan Opera to its latest staging of this popular work, placing the action into the mise-en-scène of a fantasy of silent characters never mentioned or imagined in the original libretto who are nothing more nor less than contemporary European archeologists uncovering (read: raiding) an ancient Egyptian tomb, some of whose thefts will wind up in private hands, élite auction houses, and/or eventually in the great museums of London, Paris, Berlin and New York.

It was that kind of liberatory approach to opera that I was expecting from this collection of edited addresses Said gave on four major operas originally delivered as the Empson Lectures at Cambridge University in 1997. Said intended them to be published, but dealing with both his ongoing academic responsibilities and his increasingly debilitating final illness, he did not live to complete the work. Wouter Capitain, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Göttingen, wrote his doctoral dissertation at the University of Amsterdam on Said’s music-related work and was invited to edit these lectures for publication, with a generous and helpful set of elucidating footnotes. His Introduction details what went into the reconstruction of lecture notes into a finished book.

How I wish I had been a student at Columbia in 1995 to attend Prof. Said’s graduate seminar called “Opera and Society,” where he did that kind of, shall I say, “archeological musicology” on three of the works in the current book, as well as four others. On a personal note, I have to add that back in 1969 I wrote a Latin American Studies master’s thesis by that very same title, about the culture of this art form in the imperial court of Dom Pedro II in Rio de Janeiro in the 1850s, applying my still (as a 24-year-old) limited understanding of Marxism and class conflict to the subject.

Said’s four chapters treat Mozart’s Così Fan Tutte, Beethoven’s Fidelio, Berlioz’s Les Troyens, and Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. (In his course at Columbia, he included the first three plus Wagner’s Die Walküre, Verdi’s Aïda, Bizet’s Carmen, and Strauss’ Capriccio.)

Modernity with no redemptive virtue

Mozart’s big three Italian operas, written with librettist Lorenzo da Ponte (who wound up as Columbia University’s first professor of Italian literature), are Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Così Fan Tutte (Women Are Like That). Most operas, especially of that period, are based on some existing source, such as a play or even a libretto previously set by another composer, but which, in a world without copyrights, a later composer could redo. Così has no precedent, and I was amazed to learn that it derived from Mozart’s personal experience with marital infidelity (on his wife Constanze’s part when she went to Baden for a rest cure and had an affair with one of Mozart’s own students). In its day, the opera was performed in what was then modern dress, not in some far-off place of historical antiquity.

In reference once again to his friend, the opera director Peter Sellars, Said writes: “Sellars argued that, just as Mozart wrote the operas while the ancien régime was crumbling, they should be set by contemporary directors at a similar moment in our own time, with the crumbling of the American empire, alluded to by characters and settings, as well as by class deformations and personal histories that bore the marks of a society in crisis.”

Così virtually disappeared after its initial run in 1790. Its terrifying modernity underlining the subjectivity of the amorous heart with no soothing redemptive virtue—more or less an 18th-century version of the saying “if you’re not with the one you love, love the one you’re with”— disturbed its first Vienna audience then and continued to scare off potential producers for well over a century for fear of public scandal or censorship. Only in the 20th century did it cautiously enter the standard repertoire: It is, after all, Mozart at his most sublime, and considering the horrors of World War I, well, as Cole Porter put it, “Anything Goes.”

Così stands quite apart in the composer’s canon. All his other operatic works, wherever and whenever they are set, have strong moral or humanistic messages. Said turns next to Beethoven and his only opera, Fidelio, but already in the Così chapter, he reminds us that Beethoven admired Mozart hugely. We forget that he was, in fact, his contemporary—Mozart died in 1791 at the age of 35, when Beethoven was already 21. Fidelio, whose first version, titled Leonore, debuted in 1805, only 15 years after Così, can be seen, from a moral point of view, as a muscular rebuttal reinforcing the marital fidelity that Così brought under question.

Modern audiences—most anyway, I would hope—see the comic foibles of the opera as not only the work of women. It is the mastermind of the opera, the amoral Don Alfonso, who sets the entire action into motion, with the willing consent of the two male characters scheming against their two sweethearts. It really is unfair of Mozart and Da Ponte to transfer the overwhelming responsibility for marital infidelity to women when it’s men who carried out this deception and classically have most of the opportunity and social approval for it, though under the circumstances of Constanze’s escapade in Baden, perhaps we can understand. Perhaps a more accurate title would be Così Fan Tutti (Everyone’s Like That).

From revolution to restoration

Fidelio is the story of Florestan, an imprisoned defender of the truth and mortal opponent of the dictator Pizarro (the story is set in a mythical Spain, which Protestant Europe deprecated for its long-lasting Inquisition). Beethoven took the story from Jean-Nicolas Bouilly’s play Léonore, ou L’amour conjugal. The hero, found in a dungeon on the verge of death by starvation, is a victim of such tyranny. The opera premiered as “Leonore” in 1805 and was first conceived when Beethoven was feeling a rush of enthusiasm for the French Revolution. The final form of the opera in 1814 debuted as the Congress of Vienna was gathering, the conclave that posited an end to the revolutionary era and restored monarchical governance. In the end, Leonore is successful, Florestan is rescued, the tyrant is defeated, and order (now under “enlightened” rulers) is restored.

Though Beethoven’s only opera has never gone out of the repertoire, and musically deserves its popularity, an uneasy conflation of liberatory and ultimately conservative messages in the opera might leave listeners feeling unconvinced. Its single-mindedness—the relentless effort Leonore makes to free her husband—can get a little tedious and predictable, but the plot involves some comic elements with the jailer Rocco, his daughter Marzelline, and her suitor Jaquino. Marzelline, however, is in love with “Fidelio,” Leonore in male disguise. In some ways, I believe, the only really interesting character in the opera is Rocco, a well-intentioned, outwardly decent man who is forced to do things against his inclination: His struggle for decency at least has some nuance and inner conflict, reflecting a generalized state of mind for most of us who must survive and get along in systems we don’t love. Marzelline and Jaquino have a way of pulling at our heartstrings more tenderly than the heroic, perhaps even histrionic, wife and husband.

A pageant to celebrate imperial aspiration

Hector Berlioz is a sort of underdog of French music, a visionary experimenter whose monumental five-act opera Les Troyens (The Trojans), Said’s third chapter, can be compared in ambition and scope to Wagner’s four-opera cycle, the Ring of the Nibelungen. Based loosely on Virgil’s Aeneid, the opera has never found a solid place in the repertoire, although concertgoers and radio listeners will likely have encountered the “Royal Hunt and Storm” music from it.

It’s a huge, sprawling work in the French grand opera style, composed between 1856 and 1858, that shifts scene from Troy to Carthage, where the fleeing Aeneas finds love and refuge with Dido, until he is called—repeatedly—to proceed on to “Italie” and found the Roman Empire.

Said makes much of the point that France is, after all, a Latin country, and by telling this emotionally powerful story of love and nation-building and patriotism, Berlioz can help his audience draw the connection between Rome’s ancient glory and France’s late 18th and then all of the 19th-century imperial aspirations. Not coincidentally, even as early as the Revolutionary days, the French adopted Roman styles and customs. Napoleon’s first venture abroad was his expedition to Egypt. Apart from its early holdings in the Caribbean and North America, it was in 1830 that France expanded into North Africa—Carthage is in present-day Tunisia—in a rapacious adventure to secure the region’s resources for its own enrichment. And in the true spirit of what Said calls “Orientalism,” here are natural settings with “inferior” people in the “exotic” east for the composer to exploit, as other French composers such as Bizet and Delibes would also.

Said makes much of the point that France is, after all, a Latin country, and by telling this emotionally powerful story of love and nation-building and patriotism, Berlioz can help his audience draw the connection between Rome’s ancient glory and France’s late 18th and then all of the 19th-century imperial aspirations. Not coincidentally, even as early as the Revolutionary days, the French adopted Roman styles and customs. Napoleon’s first venture abroad was his expedition to Egypt. Apart from its early holdings in the Caribbean and North America, it was in 1830 that France expanded into North Africa—Carthage is in present-day Tunisia—in a rapacious adventure to secure the region’s resources for its own enrichment. And in the true spirit of what Said calls “Orientalism,” here are natural settings with “inferior” people in the “exotic” east for the composer to exploit, as other French composers such as Bizet and Delibes would also.

“I do not want to suggest that Berlioz was an imperialist in a chauvinistically, reductive sense,” Said writes, “any more than I want to argue that Les Troyens is a crudely ideological opera. Nevertheless, I believe that it is incomprehensible as a great work of art without some account of the heady grandeur it shares both with Virgil as the poet of empire and with the imperial France in and for which it is written. The overall theme is the obligation to serve the idea of imperial destiny, no matter the terrible human costs, which, I think, even Berlioz realized were not so easy to slough off.”

Said’s analysis of Les Troyens recognizes this unwieldy pageant as perhaps the pinnacle of French operatic achievement in spite of itself. Unspoken, but implied, is his fervent prayer that one day an opera director with the right social consciousness might come along—Peter Sellars, perhaps?—to properly situate it in a convincing time and place.

Fearing the loss of authentic tradition

Finally we get to Richard Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Wagner stands in a category with Abraham Lincoln, Napoleon Bonaparte, Jesus, and a small handful of others about whom whole libraries of books have been written. In the postwar years, writers about Wagner have centered on his well-known anti-Semitism. Holocaust survivors recall Wagner’s music being blasted in the death camps where Jews were herded en masse into ovens, and Israel still has an unofficial ban on public performance of his music.

Said acknowledges the importance of this issue to many opera lovers, but doesn’t find in the music itself the kind of evidence that polemicists claim, for example, that the unlikeable character of Beckmesser is intended to be read as Jewish. Said’s focus is elsewhere.

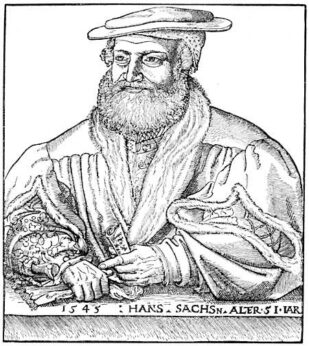

Meistersinger is the only opera Wagner wrote in a realistic setting, the historical Nuremberg of the 16th century. He chose that city as the truest embodiment of authentic German culture, and it comes as no surprise that Hitler staged some of his famous rallies there. Wagner wrote it between the years 1861 and 1867, a time before the unification of German states that created the modern Germany as we know it.

Those familiar with Wagner’s oeuvre and legacy will know that he experimented with tonality in ways that reflect the otherworldliness of his stories. Audiences of his time swooned in heady ecstasy listening to Tristan und Isolde, for instance, waiting for five hours to hear his unresolved chord finally come home to a resolution. But Meistersinger employs a far more traditional palette of sonorities, and its hero, the shoemaker and mastersinger Hans Sachs, was a beloved historical figure. In short, Wagner chose Nuremberg as the quintessential locus of German-ness. And he features the creation of music itself—beautiful song—and the men who create it, and the women who inspire it, as the opera’s theme. Without gods, kings, princes, and phantoms, river maidens and swamp creatures, Meistersinger is populated with real people in an idealized kind of middle-class German Middletown who are striving to preserve what is good in art, love, and grace.

In words that illustrate Said’s expansive mind and approach to this treacherous material (and that conclude his book), he says that Hans Sachs’s “warnings against the threat of foreign rule are not likely to endure him to proponents of hybridity and multiculturalism. Yet what he warns about is the extremely commonplace fear of the loss of authentic tradition; to today’s audience, this presents no particularly unfamiliar aspect of public discourse since it seems to be there in every kind of nationalist and/or identity politics. To ascribe it to something uniquely German, and therefore proto-fascist, is insidious to say the least, since no nationalism that I know of can escape criticism on that score. The question is whether the opera is parochially only about German art and tradition, or whether to non-German audiences it makes more universal sense than that. I certainly think so, but I think also that its message of a proclaimed national integrity is vulnerable to the kind of distortions for which the infamous Nuremberg racial laws and the Nazi era itself provide the most damning evidence. Yet in Sachs’s plea for art and a flexible understanding of its rules, we are well-placed today to discern a countertruth coexisting with the putative xenophobia that Sachs seems to be upholding. For the modern interpreter, it suffices to see the two possibilities, and then to emphasize the more humane one over the other without obliterating what still unsettles and disturbs us about this complex, bristling work of genius.”

To conclude, I’d like to give the last word back to Peter Sellars, again speaking about Aïda:

“Verdi was a committed revolutionary, visionary composer. Nearly every one of Verdi’s operas involves a political assassination in the name of resisting an occupying army—a tacit and well-understood metaphor for sustained resistance to the Austrian Army, which had rendered Italy an occupied territory in Verdi’s lifetime. I must admit that Aïda always struck me as music to open a shopping mall. Then, a few years ago, I went to Venezuela to see El Sistema ‘in action’ and attended a concert where Claudio Abbado conducted seven hundred kids who had grown up in difficult, violent neighborhoods and knew the meaning of poverty. When they played the triumphal scene from Aïda, fifty kids stood up, brandishing their trumpets, and blasted those fanfares with swing, syncopation, and a swagger, a defiance, an exhilaration that announced to everyone that a new world was arriving, and that they were the liberators. We were all blown away, and I suddenly had to change my mind about Aïda in a blazing new context.”

For anyone with a serious interest in opera, highly recommended!

Edward W. Said

Said on Opera

Edited by Wouter Capitain, foreword by Peter Sellars

Columbia University Press, 2024

Paperback, 155 pp.

ISBN: 9780231212014